- Calls to this hotline are currently being directed to Within Health, Fay or Eating Disorder Solutions

- Representatives are standing by 24/7 to help answer your questions

- All calls are confidential and HIPAA compliant

- There is no obligation or cost to call

- Eating Disorder Hope does not receive any commissions or fees dependent upon which provider you select

- Additional treatment providers are located on our directory or samhsa.gov

Binge Eating Disorder & Type 2 Diabetes Considerations

Binge-eating disorder (BED) and it’s related behaviors have been found to co-occur with some medical conditions, including type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Researchers have placed heavy emphasis on a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) as being responsible for part of this relationship. [1]

A recent study by Papelbaum and colleagues published in September of 2019 states: [1]

“Eating behavior is an important aspect related to diabetes treatment… Whether the presence of eating psychopathology has a negative impact on glycemic control of T2DM patients is a subject of controversy. Our study evaluated the relationship between eating disorder (ED) and glycemic control (and other metabolic outcomes) in patients with T2DM. We found that patients who exhibited binge eating-related eating psychopathology had worse glycemic levels than those without an ED in the presence of a higher Body Mass Index (BMI)… Nevertheless, it is not possible to rule out that diabetes-specific treatment features and the intermittent natural course of binge-eating psychopathology could also have influenced some of the results.”

What researchers, including Papelbaum and colleagues, have failed to highlight is the complex relationship between Binge Eating Disorder and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Body Mass Index. Moreover, this oversimplified emphasis on BMI can be harmful to individuals who have BED and T2DM.

The Complex Relationship Between Body Mass Index, Binge Eating Disorder and Type 2 Diabetes

It is true that the majority of people with T2DM fall into BMI categories of “overweight” or “obese.” But, it is also true that insulin resistance, one of the main underlying problems in T2DM, encourages weight gain. In fact, weight gain may actually be an early symptom, rather than a primary cause, of T2DM. [8]

If we take an even closer look at the relationship between T2DM and BMI, we see that in people with T2DM (or prediabetes), whose pancreases still make insulin, the body’s response to high blood glucose is to make and release more insulin, resulting in hyperinsulinemia, or higher-than-normal blood insulin levels. [8]

Hyperinsulinemia may promote weight gain in three ways:

- By causing increased storage of glucose as fat

- By interfering with the action of the hormone leptin, which normally signals the brain that the body has had enough to eat

- By increasing the pleasure derived from food, even when the body does not need more calories

Given these mechanisms, it’s not surprising that many people gain weight when they have T2DM. [8]

Given these mechanisms, it’s not surprising that many people gain weight when they have T2DM. [8]

Adding to this complexity, these same physiological mechanisms also appear to play a role in the etiology of BED.

Also, we know that people struggling with eating disorders may show signs of blood sugar disturbances or fluctuations and other medical issues as a result of their eating patterns and behaviors. [12, 13]

In a nutshell, the notion that, in those with BED and T2DM, a higher BMI is directly responsible for T2DM is an oversimplification. The reality is that the relationship between BMI, T2DM, and BED appears to be complex, and much more research on the topic is needed.

How the Emphasis on BMI Can be Harmful

It is easy to forget that correlation, like the positive correlations found between BMI and BED in T2DM patients [1], does not prove causation. It is common to blame health concerns like T2DM on weight and thus focus on weight-loss efforts as a means to treat the condition.

We can lose sight of many of the factors that individuals at higher BMIs face — genetics, dieting history, fitness levels, health care barriers, stress, discrimination, and poverty. These factors play a role in many of the diseases, like diabetes, that get blamed on weight. [5, 6]

Due to this wrongful emphasis on BMI, a common recommendation to improve T2DM are weight-loss focused and are often centered on maintaining a low-carbohydrate and low-sugar diet. This recommendation is particularly harmful to those struggling with BED because diets such as these can exacerbate the disorder. [7, 11]

Moreover, weight loss appears to be a short-term solution for managing T2DM rather than a long-term health maintenance strategy. A review of controlled weight-loss studies involving people with T2DM showed that initial improvements in glucose control were followed by a return to the starting levels of glucose control within 6 to 18 months.

This includes the few cases where weight loss was maintained. With that, it’s important also to note that diets are not effective for long-term weight loss or health management. [8, 9, 10]

The Recovery Dilemma: Two Opposing Treatment Goals

While the interventions to decrease BMI and improve T2DM are often focused on restricting carbohydrates and sugars in one’s diet, the interventions to improve BED often require individuals to expose themselves to foods that are often restricted.

For many, this usually consists of carbohydrates and sugars.

For many, this usually consists of carbohydrates and sugars.

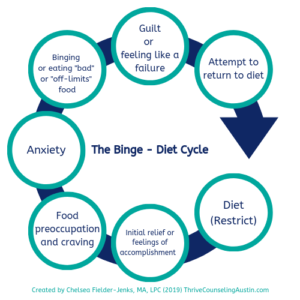

In BED treatment, this type of food exposure allows individuals to overcome what is known as the “Binge-Diet” or “Binge-Restrict” cycle (see illustration of cycle at right).

This food exposure disrupts the binge-diet cycle as it allows BED sufferers to learn that all foods can be appropriate when included in a balanced diet. They can also learn that with practice, “trigger” foods do not need to be feared nor restricted, and eating them does not have to result in a binge.

Recognizing these opposing treatment goals, we can begin to realize that recovering from BED while also managing T2DM can be a challenge.

Recovering from and Managing Binge Eating Disorder and Type 2 Diabetes

Tina Laboy, a Licensed Dietitian and Certified Eating Disorder Registered Dietitian in private practice in Austin, Texas, recommends something other than prescribing a low-carb, low-sugar diet to manage T2DM (for those with and without BED). She suggests a more effective, long-term treatment utilizing an evidence-based intuitive eating, non-diet approach to be used.

“With intuitive eating,” Laboy explains, “medical disruptions and blood sugar disturbances, in most cases, can be resolved over a period of time.” Laboy continues, “Research shows long-term health improvements are made with behavioral changes through the intuitive eating, non-diet approach.” [2-4]

Moving toward a more holistic treatment that treats all aspects of a person (rather than a superficial characteristic like weight) and that focuses on specific health behaviors, provides a more effective approach to health management. [4 – 8]

Laboy recommends individuals struggling with BED and/or T2DM receive a thorough assessment that considers health behaviors, like eating and exercise behaviors, as well as mental health factors.

“This type of approach,” Laboy adds, “allows us to actually help individuals that are struggling…when we solely focus on the surface items like weight, BMI, and blood sugar, we are doing the individual a disservice and not addressing the true behavioral struggle.”

Laboy shares her approach for treating individuals struggling with BED and T2DM, “My approach stays the same as any other individual wanting to heal from their eating disorder.

Yes, I do focus on individual health concerns, but my philosophy stays the same.

Meaning, I guide clients towards intuitive eating through a non-diet approach, focusing on behavior change so that the individual can learn how to manage their cravings, hunger and fullness, body signals, and, in this case, blood sugar without dieting or restricting themselves.”

Laboy explains, “In this intuitive eating approach, individuals will learn how to connect to their body — recognizing that certain foods with high glycemic indexes feel different from those with lower glycemic indexes. Simultaneously, working with a therapist, an individual can focus on the emotional issues that are driving/contributing to their eating struggle.”

Sources:

- Papelbaum, M., Et al. (2019). Does bing-eating matter for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients? Journal of Eating Disorders, 7 (30). Retrieved from https://jeatdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40337-019-0260-4#ref-CR2 on October 3, 2019.

- Anderson, J. W., Konz, E. C., Frederich, R. C., & Wood, C. L. (2001). Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 74(5), 579–84. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11684524 on October 3, 2019.

- Wing, R. R., & Phelan, S. (2005). Long-term weight-loss maintenance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82(1 Suppl), 222S– 225S. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16002825 on October 3, 2019.

- Bacon, L, Van Loan M, Stern JS, Keim N. Size acceptance and intuitive eating improve health for obese Female chronic dieters. J of Amer DieteticAssoc 2005;105:929-936. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3041737/ on October 3, 2019.

- Bacon, L. And Aphramor, L. (2014). Body Respect: What Conventional Health Books Get Wrong, Leave Out, and Just Plain Fail to Understand about Weight. Dallas, TX: BonBella.

- Wann, M. (2012) Health at Every Size. New York Times article, retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2012/05/07/women-weight-and-wellness/health-at-every-size on October 3, 2019.

- Platka-Bird, L. Intuitive Eating and Diabetes. Retreived from http://www.diabulimiahelpline.org/uploads/2/5/0/7/25075632/2015-02_intuitive_eating_article_-_chs-2.pdf on October 3, 2019.

- Bacon, L. & Matz, J. (2010). Intuitive Eating: Enjoy your food, respect your body. In Diabetes Self-Managment. Retrieved from https://lindabacon.org/pdf/BaconMatz_Diabetes_EnjoyingFood.pdf on October 4, 2019.

- Mann, T., Tomiyama, A. J., Westling, E., Lew, A.-M., Samuels, B., & Chatman, J. (2007). Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. American Psychologist, 62(3), 220-233.

- Pietiläinen, K. Et al. (2011). Does Dieting Make You Fat? A Twin Study. International Journal of Obesity, 36, 456–464, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2011.160

- National Eating Disorder Association. Learn: Binge Eating Disorder. Retreived from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/by-eating-disorder/bed on October 3, 2019

- Rege, S. (2019). Neurobiology of Binge Eating Disorder – A Synopsis. Retrived from https://psychscenehub.com/psychinsights/neurobiology-of-binge-eating-disorder/ on October 4, 2019.

- National Eating Disorder Association. Health Consequences. Retrieved from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/health-consequences on October 4, 2019.

About the Author:

Chelsea Fielder-Jenks is a Licensed Professional Counselor in private practice in Austin, Texas. Chelsea works with individuals, families, and groups primarily from a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) framework.

Chelsea Fielder-Jenks is a Licensed Professional Counselor in private practice in Austin, Texas. Chelsea works with individuals, families, and groups primarily from a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) framework.

She has extensive experience working with adolescents, families, and adults who struggle with eating, substance use, and various co-occurring mental health disorders. You can learn more about Chelsea and her private practice at ThriveCounselingAustin.com.

The opinions and views of our guest contributors are shared to provide a broad perspective of eating disorders. These are not necessarily the views of Eating Disorder Hope, but an effort to offer a discussion of various issues by different concerned individuals.

We at Eating Disorder Hope understand that eating disorders result from a combination of environmental and genetic factors. If you or a loved one are suffering from an eating disorder, please know that there is hope for you, and seek immediate professional help.

Published on October 8, 2019, on EatingDisorderHope.com

Reviewed & Approved on October 8, 2019, by Jacquelyn Ekern MS, LPC

The EatingDisorderHope.com editorial team comprises experienced writers, editors, and medical reviewers specializing in eating disorders, treatment, and mental and behavioral health.