- Calls to this hotline are currently being directed to Within Health or Eating Disorder Solutions

- Representatives are standing by 24/7 to help answer your questions

- All calls are confidential and HIPAA compliant

- There is no obligation or cost to call

- Eating Disorder Hope does not receive any commissions or fees dependent upon which provider you select

- Additional treatment providers are located on our directory or samhsa.gov

Instant (Chemical) Messenger: Anorexia and the Chemical Communication of the Brain

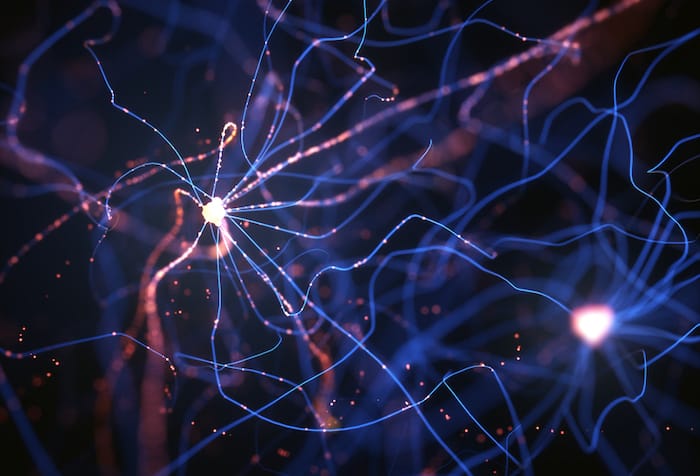

Everything we do, say, think, and feel, originates in our brain. Our brains are composed of small cellular units called neurons. Neurons are cells that process all of the information that moves into, out of, and within the central nervous system. How we act, feel, eat (or don’t), is determined by how our brains are “wired;” and how our neurons connect and communicate with each other.

Hundreds of billions of neurons forming trillions of connections in the brain are arranged into various systems that work in unison to control our mind-body functions.

Neurons connect and communicate with each other via the release, absorption, and reuptake (reabsorption) of chemicals called neurotransmitters. The brain houses many different types of neurotransmitters which respectively influence our bodily processes, behaviors, thinking, and emotions. In this article, we will focus specifically on how the following neurotransmitters have been shown to function within the brains of individuals diagnosed with anorexia: serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine.

The Structure of Neurotransmitters

First, there are several systems and structures in the brain that are responsible for and affected by these neurotransmitters, and these areas of the brain differ in those with anorexia.

Brain structures like the hippocampus, amygdala formation (responsible for emotional arousal and memory modulation)1, and the pituitary gland (which regulates hormones that control metabolism, body temperature, menstrual cycle, blood glucose levels, and bone mass)2 have been found to be reduced in size and volume in individuals with anorexia.

Serotonin

Serotonin is responsible for feelings of happiness and calm: too much serotonin can produce anxiety, while too little may result in feelings of sadness and depression. Research has shown that individuals who are susceptible to developing anorexia may present with atypical activity in the serotonin system.

This results in greater levels of serotonin compared to individuals who do not develop the disorder3,4. High levels of serotonin may result in heightened satiety (it’s easier to feel full), anxiety, and depressed mood. Starvation and extreme weight-loss decrease levels of serotonin in the brain. The result: temporary alleviation from negative feelings and emotional disturbance which reinforces anorexic symptoms5.

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is the “fight or flight” neurotransmitter. It affects the brain regions involved in fear and stress responses. This neurotransmitter helps regulate critical body functions such as heart rate and breathing. A recent study suggests that poor regulation in the system that releases norepinephrine may lead to dysfunction in the insula6, a structure in the brain that integrates the mind and body.

Chemical dysfunction in this structure may lead to distorted body image, which is a key feature of anorexia. Low levels of norepinephrine have also been linked to symptoms of depression, a characteristic concurrent experience for individuals with anorexia7,8.

Dopamine

Dopamine is primarily responsible for pleasure and reward, and in turn, influences our motivation and attention. It should be no surprise; therefore, that dopamine has been implicated in the symptom pattern of individuals with anorexia, specifically related to the mechanisms of reinforcement and reward in engaging in anorexic behaviors (such as restricting food intake).

Several studies have noted altered dopamine activity in the brains of individuals with anorexia as well as those who have been diagnosed in the past9,10. It has been suggested that the dysfunction of the dopamine system contributes to character traits and behaviors of individuals with anorexia which include: compulsive exercise, the pursuit of weight loss, as well as difficulties with attention and emotional regulation11.

Conclusion

The neurological contributions to the disorder as indicated in this overview are simplified, but in reality, the interactions of these neuronal systems are complex and nuanced. One’s brain-based biological disposition to anorexia is coupled with distinct personality traits such as perfectionism and characteristic ways of thinking. Psychosocial stressors then present to activate these vulnerabilities which drive characteristic anorexia diagnostic behaviors.

One important implication of these studies is that there is a clear relationship between the structure and function of the brain and anorexic symptoms. Prolonged, untreated symptoms appear to reinforce the chemical and structural abnormalities in the brains seen in those diagnosed with the illness.

It is therefore evident that this illness is not likely to resolve on its own. If you or a loved one is struggling with anorexia it is important to select a program, such as The Renfrew Center, that specializes in treating eating disorders and that can offer medical, psychiatric, and psychological support.

Contributor: Shawn Lehmann, MS & Rachel Dore, PsyD

About the Authors:

Mr. Lehman earned his Master’s degree in Experimental Psychology from Central Michigan University. His research has focused on cognitive deficits in individuals with depression, food allergies in eating disorder populations, and the influence of social media.

Dr. Dore’s tenure at Renfrew began in 2008: She has served as a residential counselor and intake assessment coordinator; she completed her Doctoral Dissertation research at Renfrew, followed by a Post-Doctoral Residency where she served as a Primary Therapist. Dr. Dore holds Masters of Arts and Doctor of Psychology degrees in Clinical Psychology from Widener University.

References:

- Giordano, G., Renzzetti, P., Parodi, R., Foppiani, L., Zandrino, F., Giordano, G. & Sardanelli, F. (2001). Volume measurement with magnetic resonance imaging of hippocampus-amygdala formation in patients with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 24, 510-514.

- Doraiswammy, P., Krishnan, K., Boyko, O., Husain, M., Figiel, S., Palese, V., . . . Ellinwood, E. (1991). Pituitary abnormalities in eating disorders: further evidence from MRI studies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmachology and Biological Psychiatry, 15, 351- 356.

- Varnas, K., Halldin, C., & Hall, H. (2004). Autoradiographic distribution of serotonin transporters and receptor subtypes in human brain. Human Brain Mapping, 22, 246–260.

- Kaye, W. H., Gwirtsman, H. E., George, D. T., & Ebert, M. H. (1991). Altered serotonin activity in anorexia nervosa after long-term weight restoration. Does elevated cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid level correlate with rigid and obsessive behavior? Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 556–562.

- Kaye, W.H., Fudge, J.L., & Paulus, M. (2010). New insights into symptoms and neurocircuit function of anorexia nervosa. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10, 573-584.

- Nunn, K., Frampton, I., & Lask, B. (2010). Anorexia nervosa – A noradrenergic dysregulation hypothesis. Medical Hypotheses, 78, 580-584.

- Delgado, P.L. & Moreno, F.A. (2000). Role of norepinephrine in depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61, 5–12.

- Nutt, D.J. (2008). Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 4–7.

- Frank, G.K., Bailer, U.F., Henry, S.E., Drevets, W., Meltzer, C.C., Price, J.C.,… Kaye, W.H. (2005). Increased dopamine D2/D3 receptor binding after recovery from anorexia nervosa measured by positron emission tomography and [11c]raclopride. Biological Psychiatry, 58, 908-912.

- Kaye, W.H., Barbarich, N.C., Putnam, K., Gendall, K.A., Fernstrom, J., Fernstrom, M.,… Kishore, A. (2003). Anxiolytic effects of acute tryptophan depletion in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33, 257-267.

- Phillips, M., Drevets, W. R., Rauch S. L., & Lane, R. (2003). Neurobiology of emotion perception I: The neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 504–514.

Last Updated & Reviewed By: Jacquelyn Ekern, MS, LPC on July 22nd, 2015

Published on EatingDisorderHope.com

Articles on Anorexia

- Understanding Anorexia Treatment: What to Expect During the First Week in Residential Treatment

- Anorexia and Emotions: A Treatment Approach From the Inside Out

- Anorexia Recovery and Overcoming Physical Side Effects of an Eating Disorder

- Common Signs & Symptoms of Anorexia

- Does Anorexia Impair One’s Ability to Relate Socially?

- Anorexia and Infertility: Causation or Correlation

- A Whopping 95% of all Diets Fail: Is it Anorexia in the Making?

- Anorexia & BMI: Is Weight the Sole Determiner of Anorexia?

- Dieting and Recovery from Anorexia Nervosa – Do They Mix?

- Meal Time Tips for Families Struggling With Anorexia.